It is a very sophisticated tool. It is called Taiji Quan because it is a martial art based on Taiji the philosophical principle. We can think of Taiji Quan as an app for Taiji the concept as it is applied in the area of martial art. For this reason, it is always said the highest purpose of taiji quan is by doing this physical practice guided by Taiji idea, we come to understand Taiji, and the larger picture it is a critical part of - Dao. This is similar to what people do with yoga - concepts are abstract, a student need concrete examples to practice the idea, and with enough practice, understand the underlying idea.

Then the key question is what is Taiji. It's not enough to say it's an interplay between Yin and Yang. That would be too broad: wu xing is interplay between yin and yang, so is ba gua. Taiji specifically is yin and yang existing at the same time within one entity. If they are separate entities, that's called liang yi. Example: if someone pushes toward our left arm, we first move that arm away (yin), then attack him in some way (yang), that's an example of liang yi. This is how every other martial art operates. That obviously can work. We can definitely use that to win fights (effectiveness). But it is not considered Taiji skill.

To be considered application of Taiji principle, we need to do yin and yang the same time. So let's talk about that yin part first: in the above example, if someone pushes our left upper arm, we do not attempt to resist with that arm (fight), or move it away (flight). Doing either means we are actively guiding the action of that spot where the opponent is attacking (he is yang in that spot, that is where his mind is). Try to solve the problem directly on our trouble spot meant we are putting our mind there as well. So we have a yang on yang interaction. This is called double-weightedness, which, according to taiji the philosophical concept, is not the most efficient way to solve conflicts. So even merely thinking "don't resist with this arm" is wrong, because the key thing is our mind is still there.

So what is real yin then? Yin means passive. Passive means you have no mind - no idea of your own. If you're visiting a friend, and he asks you to follow him in your car to get to a restaurant you never even heard of, you just follow him, whereever he goes, you follow, your every action is result of his action - that is true passiveness. That's what we need to do on that spot he's attacking, you have no idea, no opinion, no wish or intention (not even "yield here, don't struggle") of any sort about that spot, it's like it has nothing to do with us. We are totally ignoring it.

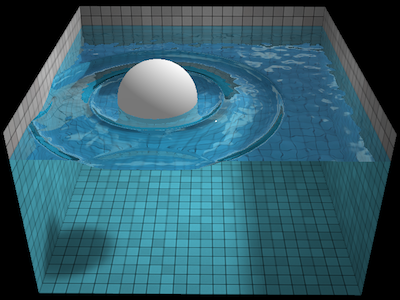

But if we just do that, it's not taiji, because it's pure yin. And just allowing the opponent to do whatever he wants to that spot will lead to us losing. Yin without yang is not softness, it's weakness. So how do we solve the problem then - by also employing yang, but in a very specific way. We use our mind to guide the action of some other part of the body where the opponent has (relatively) no influence on. By definition of Taiji philosophy, we should be yang where the opponent is yin. In Taiji we want our body to have the quality of a ball floating on water (or some other unstable surface). If we push on the ball, and our push is not perfectly through the center, we will lose balance fall to that side right? The ball doesn't have a mind, it doesn't try to change the trouble spot in some way, what is does have area all the qualities of a ball. Actions is always faster than reaction right, if they both need to travel in the same directions. One of the very few ways (this is why most people think Taiji Quan is against common sense, that it can't work) a slower reaction, a smaller force can neutralize a larger force, because it has these qualities which allows it to be touched, but not affected in the manner intended.

Our body is not literally a ball, so we have to behave in ways that emulate the ball. In the example above then, if someone pushes our left upper arm in a straight on path, we ignore that arm mostly, and instead wave our right arm as if to slap the opponent on his left cheek. This is where peng and integration comes in. Remember in the Taiji diagram within yin there's a bit of yang. That yang is peng. Peng is the force you exert to maintain the relationship between the arm being pushed with the rest of the body. To quote a often used phrase on this form - "maintain the structure". A ball cannot be a ball if it just deflates when pressed. At the same time you are integrated. Integration means no single part of our body is isolated. Every part is connected, affected, sharing the load. It means when one part moves, every other part moves. So here when you move your right hand, you are also turning your waist, which in turn turns our your left side, including the hand rotate to the left. In doing so causing his force to miss, solving the problem. Attack and defense at the same time, attack and defensive as parts of one overall motion, that is Taiji.

The interesting thing that happens here is that if you initiate this rotation with the left arm, it will not work, as the opponent will detect the change there. Here's an example that more clearly illustrate this:

grab a steering wheel with both hands at 3 and 9 o'clock, now have someone grab your left wrist, try to push it off the steering wheel by exerting a downward force. First the natural reaction: try to do struggle with that hand directly. Whatever you do, the opponent can detect it and adjust accordingly. If you try to escape by use the left hand to rotate the steering wheel down and to the right, he will either change his force to a different direction or let go immediately. But he will not lose balance. Then the Taiji way, let him grab that 9 o'clock wrist, as he is push down, do just enough to maintain grip with the steering wheel with the 9 o'clock hand, use the right hand to borrow the momentum of his downward force, and circle it back to him by turning the steering wheel toward left. Now your left wrist will leave the position from 9 to 8, or 7, to 6 naturally right. Initially he will not feel any change (your left hand is passive, not appearing to have any force at all, the hand that's generating the force he is not in touch with, so he cannot know): in fact as the wheel is turning, he rightly feels it's working, this is all his doing. But imperceptibly, the angle of contact between his hand and your hand changes, the angle becomes more and more awkward until the motion is nonviable to him, no matter how much additional force he puts in. In this example we're forcing the integration by using a physical wheel, and the strength of material of the steering wheel provide peng. In fighting our body needs to have all the qualities of that wheel. If we're not similarly integrated, waving the right hand only moves the right hand and nothing else, the opponent still wins.

This is how a smaller force can defeat a larger force, not because it can do anything directly against the larger force - but by changing the angle so that the amount of the force is not the key issue, but whether it's going to go through the target in an effective manner. It's imperceptible because a) we are borrowing his force to make this change, so he will think everything is going according to plan until too late. b) we are not trying to change him directly. We are using his force to change a small part of ourselves, and by maintaining an unthinking connection with him, he's going along with us without thinking - first we are "taking a walk" with his force, then he unwittingly takes a detour with ours. And c) the rate of change, not matter how fast or slow, is smooth and even. It's smooth and even because that's the quality of a circle. A circle is by definition a series of points equal distance from the center. As you going through a motion, the change from spot to spot in space is smooth, instead of a jagged line where it's easy to detect a change.

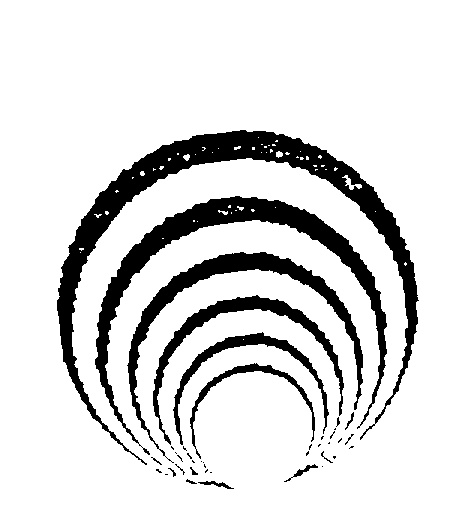

This smoothness is represented by the line between yin and yang half of the Taiji diagram. This is a major concept about change in Taiji the philosophical principle called zhuan huan. Most martial art use the other type - Cha Yi. Cha Yi is like a binary switch, it has only two states, on or off. I'm either here or not here. Zhuan Huan include all the fuzzy, partial, neither nor, has the potential to be anything states in between. This is one major philosophical idea absent from traditional Western philosophy. Taiji is the only one out of three internal martial arts to use Zhuan Huan.

Anyone who has tried to lift a heavy weight in the gym knows this feeling, even when the force is simple (in one plane only), if your change your grip a little bit, a little extra space here or there, a finger or two not quit having solid contact with the bar, the hand a little sweaty, and you cannot do what you want with that weight. When trying to manipulate a heavy object that is free to move in all three planes, even a little thing can foil it. Hence the expression "a four ounces [force] can neutralize a thousand pound [force]". Or when you play golf, the slightest error in the way you grip the club, how you positioned your feet, where your eyes are looking, and cause the ball to go wildly off in the wrong direction. In Chinese we call that "a small deviation that results in error of thousand miles" - this is the danger whenever we use large force, the more powerful the force, more accurate and sure the direction we have to be. Taiji Quan is the art of creating small deviations that results in devastating loses. Those loses are not result of not applying stronger, faster force, but that of "start off doing the right thing, then the situation changed but I didn't notice in time and just kept doing the same thing, which then became the wrong thing to do, and end up hurting myself".

So this is how Taiji works. If you have to consciously think "yield, don't struggle, redirect here", it would always be too slow for real fights. The ball has no consciousness, no strategy, what it has are qualities that are basically impossible to defeat. So while we have to practice slowly, deliberately to acquire these properties, once acquired our actual reactions are fast. They are fast because they are automatic (inherent qualities), because the actual movement is small (just a tiny change in angle of contact makes a huge difference), and they work because opponent doesn't even recognize our change until too late (his force driving all these smooth, small changes). So it's like something happened that cause our body to lose balance, and various parts of all our body just moves instantly on its own to restore it. It's that fast, automatic, natural, and spontaneous (quan wu quan, yi wu yi).

"Water is the softest substance in the world, yet it can overcome the ultimate in hardness. Every man knows this, yet who knows how to implement it?" - Laozi

Daoism is an unique product of Chinese thought, a set of beliefs about how the world/nature operated that are deeply ingrained people's beliefs. People saw in properities of water manifestation of high level principles, they strove to be in accordance with Dao in everything they do. In martial art, the 3 internal schools each found ways to apply aspects of Daoist ideas in their skills: "Taiji kong dong" (taiji makes the contact point empty), "Ba gua bian doing" (Ba Gua changes the contact point), "Xing yi heng dong" (Xing yi exerts a crossing force on the contact point). The three internal martial arts are also the only ones with the expressed goal of not just being effective (can we win fights with it), but also in the most efficient manner (how little of our own force do we need to use, in turn how many and how much bigger the opponents can be bring down...).

Daoism is amongst the most counter-intuitive and radical of philosophies - solid is not as good as empty, wisdom is foolishness, softness can overcome strengh, etc. These ideas permeate every aspect of Chinese culture, giving native speakers a huge advantage when it comes to understanding and practicing the skills. For people not exposed all of that, if they try to understand and practice these martial art based on conventional wisdom (more is always better than less) of their own culture, their system of logic (binary instead of xuan), and their common sense/everyday experience (watching popular spectator sports where the goals are to be "Faster, Higher, Stronger"), they can easily miss the mark completely. Add on top of that our increasing distance from nature - how many of us do complex manual labor every day, how many of us have the everyday experience of working on complex mechanical devices, struggling with hard to reach parts that we cannot manipulate no matter how much we try to force it...? Hence the common phenomenon of practicing internal martial art like external martial art. These postures we can all do with speed and power to win fights. But if real Taiji quan skill is what we're chasing after, we need to know first what it is, the radical philosophy it's based on. If we don't have that type of fundamental understanding, then we're liable to spending most of our time chasing the wrong things (ex. biggest fajin), leading us further and further away from deeper understandings of Dao.